Talking Shop with

Erica Heinz

UX and Product Designer in Brooklyn, NY

-

Interview by Carly Ayres

@carlyayres

-

Illustration by Ping Zhu

@pingszoo

Talking Shop is an interview series where we talk to freelancers about freelancing. In this interview, we talk to Erica Heinz, a UX and product designer in Brooklyn, New York.

Who are you and what do you do?

Erica Heinz: I’m a UX and product designer. I’ve been freelancing on and off since 2002 and have had two full-time jobs where I worked at larger organizations. Now I do a mixture of part-time for one ongoing client, then freelance the remainder.

What kind of projects do you like to work on?

I find that the best fit for me are smaller companies that have existing customers and a bit of momentum behind them, versus brand new startups. It’s less risky as a freelancer because it increases the likelihood that the work I do will be around in a couple of years.

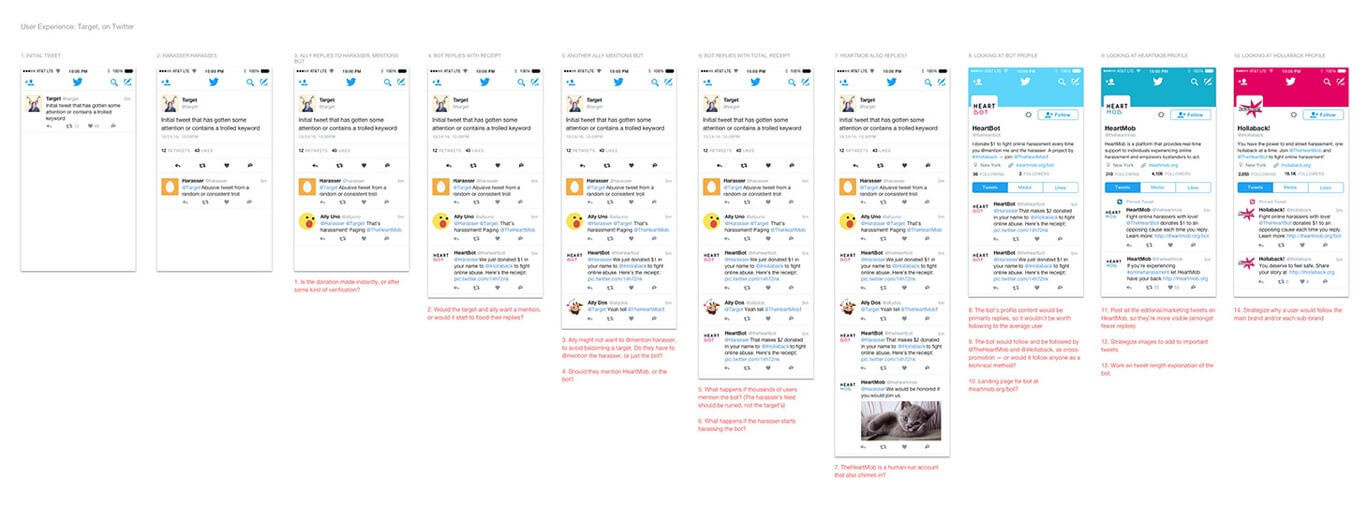

With smaller companies—say, under 50 people—I can come on as a generalist and help them develop the proper processes for their brand. I do a bit of pro-bono work, too, and just wrapped up a Twitter bot to fight online harassment (working for Hollaback! through Civic Hall Labs). Having a steady part-time client lets me take on those types of projects.

Do you remember putting together your first proposal?

It was so stressful. That moment when you're sitting at your computer thinking, “What number do I put here? What are the hours?” I would stay up until two in the morning wondering what to do.

“It’s good to start with an hourly rate until you have a sense for how long things should take. Time-tracking software is great for getting some self awareness around how long work takes.”

I keep spreadsheets where I break down each piece of a project—a contact form, a homepage, everything—line by line, so I can estimate and multiply more clearly. Over time, I’ve been able to really see how long something takes me.

How do you charge now?

Right now, I'm loving the day rates. Hourly rates make sense for small or friendly projects, where you’re comfortable being a “hired hand”. It’s often appealing for a client that has a limited budget, or wants a flexible process. It’s a good way to be transparent about how you’re working and just measure as you go.

The problem with hourly rates is that clients rarely predict how their hourly needs might vary week to week. It’s convenient for the client, but you end up cutting up your week into all these chunks and it’s on you to fill the remaining gaps. You end up with more administrative work, too. At one point (thanks to Cushion), I realized that one of my clients was 60% of my invoices and only 20% of my income. Bigger blocks are easier to arrange.

How many hours are in a day?

For me, a day is roughly six hours of heads-down, focused work, which is about what you’d get in at an (ideal) full-time job, as well. The admin stuff is outside of that, so you have to leave time for it.

Freelance rates can seem high to full-time employees, but they have to take into account all the other costs that go into running your business—health insurance, office space, internet, software, education... You’re charging for what it takes to stay on top of the technology and trends that allow you to provide stand-out value to clients..

That value goes two ways. When it comes to larger clients and bigger projects, make sure to think about how the work you’re doing will benefit them. Dan Mall wrote a good piece on this. If the client is going to make a ton of money off your work, you should be incorporating that into your rate, too.

What does that conversation with a client usually look like for you?

It’s complicated. Every job is different, the answer is always “it depends.” But I’ve definitely learned to be explicit and confirm terms. People often have different expectations for common phrases. For example, “wireframes” is one of those words that can mean anything from squares on a screen to a fully fleshed out layout.

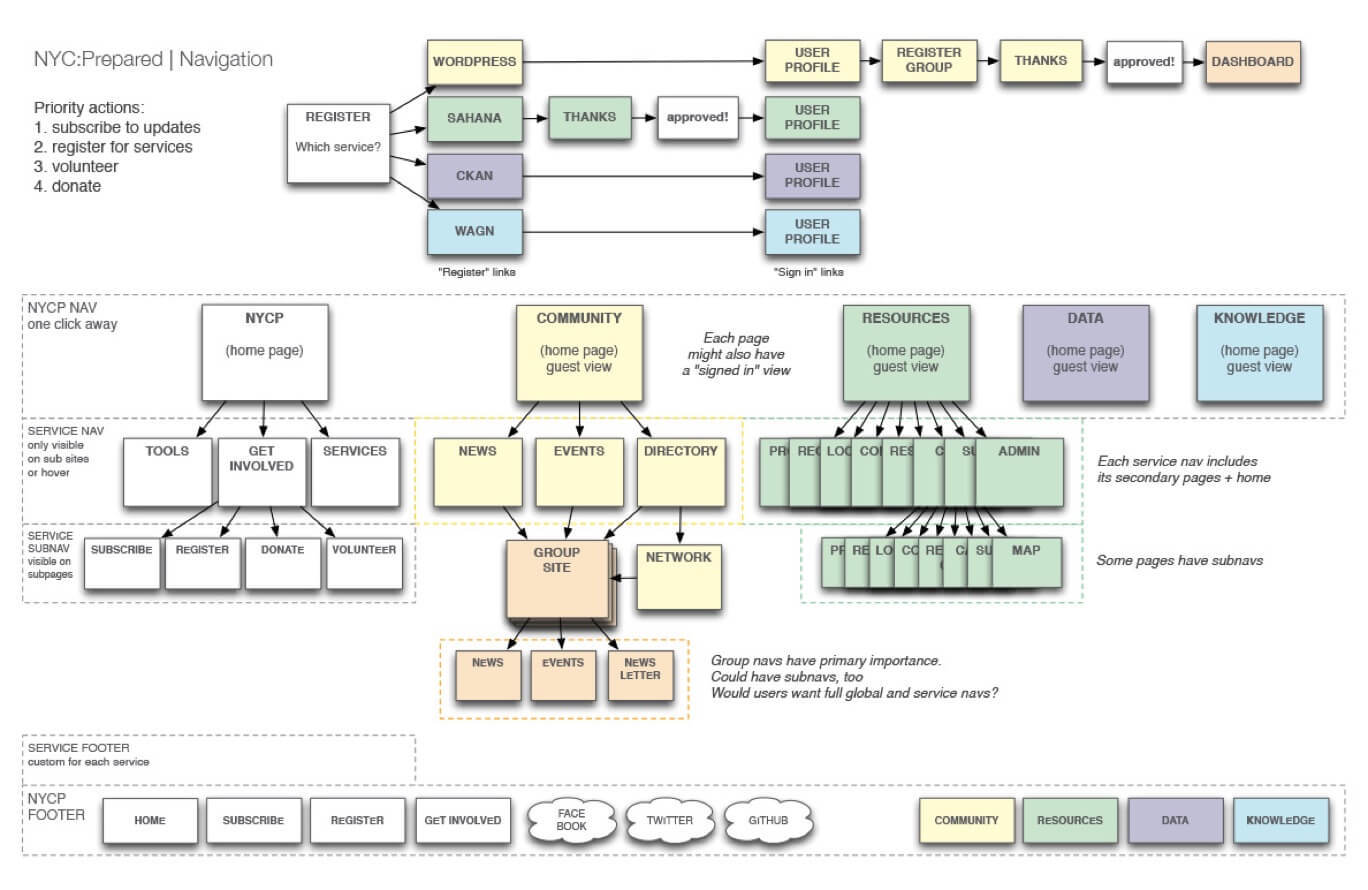

I typically begin with a discovery phase and some site-mapping, which helps me to understand the full depth and breadth of the project. I find that it helps everyone else get on the same page, too. If there’s already a backend team, they can see and advise on what we’re planning to do, and other interested stakeholders can feel like they’ve been a part of shaping that process, as well.

We’ll also know each other a bit better after that process. We’ll have a shared sense of scope and I’ll have a better idea of how complex of a project this will be. Plus, if it’s not a good fit, we’ll know, and we can break it off — you’ll still have the outlines and maps to take to another designer.

What types of questions do you ask?

I have a whole list. Most important is agreeing upon goals. How will you define success for this project? Is it to get more signups? Better usability? Even if the answer seems obvious, you want to be sure you’re absolutely aligned. Sometimes priorities completely shift after a discovery phase. You also want to know about, and hear from, any other stakeholders who might disagree or prevent this project from going out into the world.

I ask them about business goals, marketing goals—but really try to get them out of “sales pitch” mode and into a conversation where they’re actually thinking these things through. What makes your company different? How are you distinct from your competitors? What do you like about your current design? What don’t you like?

Then I make a list of priorities and have the client rank them: meeting a deadline, adding new functionality, refactoring existing stuff, creating a new image, improving key metrics, keeping costs down, understanding the audience... It helps us get through the tough reality that you can’t have all of these things all at once.

“I usually use the metaphor of apartments—is it a starter apartment, or a house you want to live in for a while? How much furnishing do you need right now, and how much can wait?”

Then we can try to scope it in. For example, for a website: What’s the budget? Where will the content come from? What additional services will you need — Copywriting? Retouching? Hosting? Who is responsible for these?

And I ask about what will happen after I leave, too. Who is going to maintain the product? What software will you use? What kind of customer support will you provide? Sometimes it brings up organizational holes that the client hasn’t even considered.

How long does this conversation usually take?

I usually try to suss some of the more critical questions before I even take on the project, through a 30-minute phone call or video chat. If they don’t have great answers to a lot of these questions, it’s likely that the project is not going to be a good fit.

The discovery phase is something I package as the first step for any work I do. It sparks insights for both me and the client, and sets a solid foundation for our work together. The scope can go up or down to include community research, surveys, testing, and more, but it’s essential for clients to carve out the time for good research and planning. We want to make the project a success — that’s the shared goal.

What’s next?

This fall I’m going to be teaching the major studio in Parsons’ new masters program in Digital Product Design, so I’m having fun preparing the curriculum and guests for that. And keeping my skills sharp on some complicated retail apps.

I’d also love to work on education in a broader sense — news, books, talks, that sort of thing. Products that help us understand and improve the world. So I’m doing some research and we’ll see where the year leads!

You can visit Erica Heinz’s website at ericaheinz.com.